Athletic Software Engineering (2017)

17 Jun 2017For the past four years, I have been developing a pedagogy called “Athletic Software Engineering” (ASE) which I use in ICS 314: Introduction to Software Engineering. This pedagogy involves a high intensity, time-constrained, and often stress-inducing approach to acquiring competency with software engineering skills. Despite those characteristics, a survey of ICS 314 students from AY 2016-2017 found that 90% of them prefer athletic software engineering to a more traditional teaching approach.

This essay presents an overview of Athletic Software Engineering as I currently teach it. I begin by explaining what motivated me to design the pedagogy. I follow this with a summary of the major features of Athletic Software Engineering, and conclude with the results of student evaluations of the method and my class.

1. Motivation

To motivate athletic software engineering, it’s necessary to first understand the goals of my software engineering course:

-

Acquire competency with a minimal technology stack for modern software application development. In the case of ICS 314, this “minimal” stack includes Javascript, git, GitHub, ESLint, IntelliJ, HTML, CSS, Semantic UI, markdown, mocha, chai, npm, Meteor, MongoDB, and Galaxy.

-

Experience “design” problems. Design problems occur at the code level (for example, how to structure code so that it is testable), as well as at the user interface level (for example, how to organize the presentation and manipulation of data so that user needs are satisfied).

-

Experience “process” problems. Process problems involve group communication and coordination, and how to define, delegate, and manage tasks such that a group of developers can work together to create a functional application in a limited amount of time.

-

Design and implement an application that solves a “real world” problem for UH students. For example, students on a meal plan are allocated a certain number of “points” each week for buying food, which disappear if unused. To solve this inefficiency, one team developed an app called “Manoa Dining Delivery”, in which students can turn their expiring points into cash by purchasing food at the cafeteria and delivering it to another student on campus. Here is a portion of their home page:

These four goals for ICS 314 build on each other: without competency with a technology stack, it is difficult to experience significant coding and user interface design problems. Significant design problems are needed in order to provide a context for teams to experience process problems. And without the ability to solve both design and process problems, it is difficult to successfully design and implement a “real world” application.

Note that developing an application to solve a “real world problem” requires a substantial portion of the semester. I find students need a minimum of six weeks to work on the final project, which leaves only 10 weeks to develop “competency” with the underlying tools and techniques. Athletic Software Engineering is designed to solve the pedagogical problem of developing competency with a significant set of tools and technologies in the time available during a semester.

2. Why “competency” is important

Consider the following development scenario, which is typical during final project development:

A student chooses a development task (Issue 23) from the GitHub Project board, and moves it from “Backlog” to “In Progress”. She then creates and publishes a new git branch called “Issue-23” off the project’s master branch in which to accomplish the task. The task involves the creation of a new page containing a form in the application. She creates a new page template in Meteor along with a route to that page, several Javascript callback functions to manage form processing, and a responsive layout for the page using HTML, CSS, and Semantic UI. To store the results from the form, she extends a MongoDB collection with new fields, and writes a test using mocha and chai. In the IntelliJ IDEA editor, she notes any ESLint code style errors as they occur and removes them. When the page works correctly, she commits her branch to GitHub, merges the results into the master branch, and moves the task from “In Progress” to “Done”.

Notice that in this (very simple) development scenario, there are nevertheless explicit references to a dozen technologies (GitHub, git, Meteor, Javascript callbacks, HTML, CSS, Semantic UI, MongoDB, mocha, chai, IntelliJ, and ESLint). There are also implicit references to design problems (What information is being manipulated on that page? Is that the right information to manipulate? Is the chosen page the appropriate place to manipulate that information?) and process problems (Is that the appropriate task for that developer to work on right now? How might that task interact with others being worked on by others in the group? What communication should be occurring to make sure the developers do not implement conflicting code?)

One key insight motivating athletic software engineering is this: if an ICS 314 student is competent with the technology stack, then and only then is it possible for that student to actively engage with “design” and “process” problems. If a student is not competent with the technology stack, then their focus devolves to understanding the technology stack, not the higher level “design” or “process” issues. For example, if a student does not understand how to implement a form in Semantic UI, then that becomes the focus of attention; it is unlikely that the student will spend the time to compare and contrast design alternatives without an understanding of how to implement any of them.

3. The intrinsic complexity of a software engineering technology stack

One question is whether ICS 314 requires an overly complex technology stack. I strive to require as minimal a technology stack as possible, such that whatever complexity results is intrinsic to the practice of software engineering. Consider that the 12 technologies can be organized into the following seven categories, which represent central concepts in software engineering:

- Programming Language (Javascript)

- Development Environment (Intellij IDEA)

- Project Management (GitHub issues and project boards)

- Configuration Management (git branch and merge)

- User Interface (HTML, CSS, Semantic UI)

- Testing and quality assurance (mocha, chai, ESLint)

- Application framework (Meteor, MongoDB)

Over the years, I have taught ICS 314 with many different combinations of technologies (Java rather than Javascript, Play rather than Meteor, Bootstrap rather than Semantic UI, Subversion rather than git, Google Project Hosting rather than GitHub, JUnit rather than mocha/chai), but these seven classes of software engineering technologies persist, as well as the need to obtain competency with them in order to experience “design” and “process” problems.

4. Efficient and effective development of competency

Athletic software engineering is a term I created to describe a set of interrelated teaching practices whose goal is to help students develop “competency” with basic software engineering skills prior to commencing their final project. If they achieve competency with most or all of the skills, then the final project: (a) enables them to develop experience solving design and process problems; (b) makes it more likely that they will successfully implement a “minimum viable product”, and (c) results in a significantly richer educational outcome.

While a description of athletic software engineering sufficient for classroom implementation is beyond the scope of this essay, here are some key features that distinguish it from other approaches.

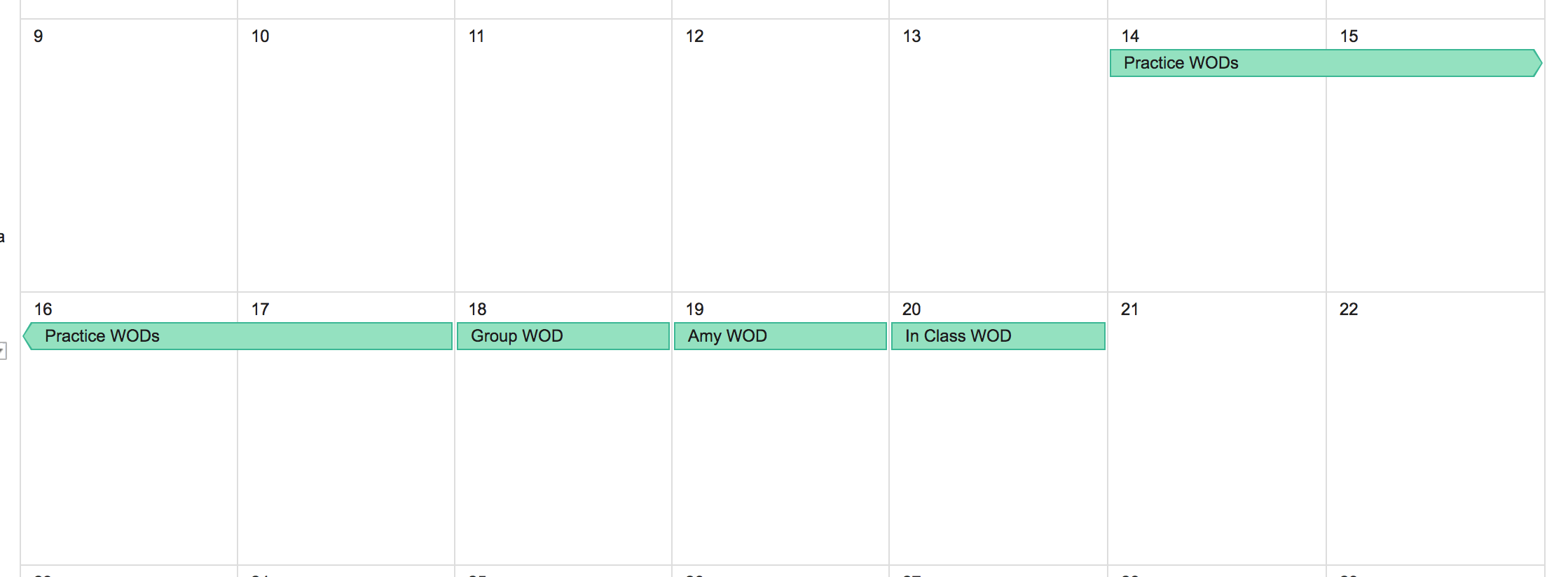

Weekly module schedule. The class is organized into a sequence of “modules”, each lasting one week. If my class meets on Tuesdays and Thursdays, then each module begins on Friday and lasts until the end of class on the following Thursday. Students work on “practice WODs” from Friday to Monday, do a “group WOD” on Tuesday, an (optional) Amy WOD after that, and an “in class” WOD on Thursday to complete the module. (These WODs are described in more detail below.) Here’s an illustration:

Javascript 2 is an example of a module.

Skill acquisition, not concept acquisition. Students are evaluated based upon their ability to complete a task, not on their ability to discuss a concept. For example, a test module would evaluate the ability of a student to define and implement a unit test, not evaluate the ability of the student to describe the difference between a black box test and a white box test.

Workout of the day (WOD). I use the CrossFit term “WOD” in Athletic Software Engineering. In ASE, a “WOD” is a problem that requires the student to exercise one or more skills both correctly (i.e. such that the problem is solved) and efficiently (i.e. within a time limit). There is an upper bound on the time allowed to solve a problem (which typically makes it impossible to “google your way to the answer”.) To set the upper bound, I time myself solving the problem to establish an “expert” time, then add 50% to 100% more time to obtain the upper limit for students. This upper bound is referred to as the “DNF” time (or “Did Not Finish”). This past year, I assigned around 35 WODs each semester, which ranged from 5 minutes to 40 minutes to complete, with most WODs having a DNF time of somewhere between 10 and 20 minutes.

Practice WODs. Each module provides several “practice WODs” to be done as homework between Friday and Tuesday. Practice WODs differ from traditional homework assignments in several ways. First, each practice WOD indicates, in addition to the problem to be solved, the time limit for successful completion of the WOD. Second, each practice WOD includes a video of me solving the problem, and timing myself while doing so. Third, I typically instruct students to first attempt to solve the problem by themselves without watching my solution video, and time themselves while they do so. If they have not solved the problem by the DNF time, then they should stop at that point and watch my solution video, then try to solve the problem again from scratch, timing their second attempt as well. If they cannot complete the assignment before the DNF time again, they are instructed to review the video and keep attempting to solve the problem until they can do it within the specified time limit.

Some students admit that they do not follow this procedure, although most learn quickly that this is actually the most efficient way to acquire competency and avoid the dreaded DNF on the “in class WOD” (see below).

Jamba Juice 1 is an example of a practice WOD.

Group WOD. The Tuesday class is dedicated to one or more “Group WODs”. For each Group WOD, I randomly split the class into groups of two. I then provide a new problem for them to solve using the same skills they (hopefully) developed from the practice WODs. However, they are now working in a group, and they have to work concurrently (in most cases, I ask that they both complete typing each line of code before either can type the next one.) Once again, there is a time limit, although the limit is elevated since working concurrently can slow things down, and because I want to encourage them to discuss issues as they arise during the solution process.

The Group WOD fulfills several pedagogical goals. First, it provides a self-assessment procedure for students; they can see if their work on the practice WOD has actually prepared them to successfully solve a new problem. Second, it provides an engaging classroom learning environment; rather than working silently alone, they get to work with another student. By the end of the semester, most students have had 1-on-1 time with most other students in the class. Third, it incentivizes students to do the practice WODs, since they know that they will need to demonstrate the skill in class in Tuesday with another student, and this creates social pressure to prepare. Finally, doing the Group WOD helps the students acquire more competency with the skill itself.

BK Menu is an example of a Group WOD.

Amy WOD. During academic year 2016-17, my TA’s first name was Amy and she held a weekly, voluntary meeting to provide another opportunity to do a timed WOD. Amy WODs are individual and timed, and after the conclusion she goes over the solution. Amy WODs were usually on Tuesday or Wednesday afternoons or evenings, after the students had (hopefully) finished the Practice and Group WODs.

Pokemon is an example of an Amy WOD.

In class WOD. The Thursday class period ends the week-long module, and it consists primarily of the “in class WOD”, which is yet another individual WOD, but this time it “counts”: almost all of the points for the module are based upon the student’s ability to solve the problem presented in the In Class WOD both correctly and within the specified time limit. In class WODs are generally graded on an “all or nothing” basis: if you solve the problem correctly and within the time limit, you get 100% of the available points. If you don’t, you get zero. Early in the semester, it is possible for up to half the class to DNF on the in class WOD. As students learn how to acquire competency effectively, this percentage tends to drop. Most semesters there is at least one in class WOD where no student DNFs.

Bar Tab is an example of an in-class WOD.

The combination of extensive “training” throughout the week in the form of practice, group, and Amy WODs, followed by a single “performance” to demonstrate the skill, is similar to many athletic (and artistic) disciplines. It is designed to help students learn to take the “training” seriously, just as athletes (and artists) take training seriously, because it is the only way to increase the odds that they will succeed at “game time”.

5. Student evaluation of Athletic Software Engineering

Most students report that the WOD-based athletic software engineering pedagogy is very stressful. To obtain a detailed perspective, I ask students each semester to complete a questionnaire about their view of WODs and Athletic Software Engineering. Here are the results for AY 2016-2017.

There were a total of 119 students across the four sections of ICS 314, and 86 filled out the survey, for a 72% response rate. The following sections present data from the most relevant questions:

Do you prefer ASE to the traditional way of teaching?

90% of the students surveyed prefer Athletic Software Engineering. Positive comments include:

- I got accepted to an internship from a company and they put me through 3 rounds of ‘WODs’ to test me before giving me the offer. I think the WODs in 314 helped.

- Something I’ve noticed in my 111 and 211 class is a lot of people having a terrible time because the student wouldn’t put forward enough time outside of class to practice, resulting in a poorer performance in class. Athletic software engineering promotes programming as a more of ‘way of life’ (because it requires a lot of outside practice before you get comfortable with any framework) than a homework assignment like a math problem set or English paper.

- The pressures that come hand in hand with learning by the way of athletic software engineering compelled me to put more time and effort into learning and practicing the material than if I were to study it through a more traditional approach. It was helpful to also have many resources and videos to review at my own convenience, and at multiples times. This allowed me to learn the material at times that worked best for me, and I was able to relearn something if ever there was an instance when I needed to relearn or reference a particular concept or practice.

- I believe in learning by doing and that’s what the athletic approach is all about. In passive learning, it’s easy to think you know how to do something, without actually knowing.

About one out of ten students did not prefer ASE. Here is a comment from one who didn’t:

- I feel like the timing of the assignments for me doesn’t have a positive effect on my end product. Sometimes I feel like I learn the content for speed instead of spending the time to actually learn the purpose of the content. This is not a fault of the system, this is more a personal fault of not repeating WODs or revisiting old assignments.

Are repeating the WODs helpful?

84% of the students surveyed indicated that repeating WODs were helpful either all the time or part of the time. Positive comments include:

- Yes, in the beginning I didn’t really practice them much and didn’t perform very well, but in the middle I began to practice more and attend the Amy WODs and did a lot better.

- I found it to be useful because after practicing the same techniques over and over, I was able to have a better understanding of how to use it and apply it to various scenarios.

- Repeating the practice WODs is definitely useful. One caveat to this is that students need to do it on their own first. If they fail, view the solution, think about the solution, then try again at a later time. Repeating the WOD immediately after viewing the solution doesn’t help as much. Through repetition, I was able to memorize certain functions and lines of code that allowed me to do certain things, such as a “for-let-of” statement. Coming from traditional C/C++, I often found myself iterating through an array with a for loop instead of the convenient syntax aforementioned. Repetition of WODs is analogous to repeatedly practicing free throws; the more practice you get, the better you become.

- Yes, I definitely think repeating the practice WOD is so useful. I think I actually learn more in practice WOD than in class.

- I only repeated the practice WODs when I couldn’t finish or took too long to finish. After repeating them a second or third time, I was able to understand the material better and better each time.

Here’s a comment from a student who did not find repeating the WODs to be useful:

- No, I did not find repeating the practice WODs to be extra useful. Completing them only once was more than enough for me, and repeating them (especially after knowing the solution) didn’t help with my retention, since it’s the exact same problem.

Was the in-class, graded WOD helpful for learning?

91% of the students surveyed found the in-class WOD to help in learning. Positive comments include:

- Yes. The in-class WODs forced me to prepare and really understand the material. It also kept me motivated to finish all the homework and practice WODs on time.

- I think it was helpful because it was 100 or 0. It gave me extra motivation to find the solution and made sure it worked. If we were to receive partial credit and such, then I believe I would of settled for partial points at times.

- Yes, because this personally was the strongest motivator for me to understand the material.

- Yes. In particular I think the in-class WODs were the right size and scope. Broad enough that you’re thinking about the nature of the programming problems rather than just a sequence of steps, but limited enough that practice really does make you feel prepared.

- Having in-class graded WODs are what drove me to really take the time to study and practice the given assignments at home

- I think that the stress placed on coming to class for the WOD especially and the time constraint made us see if we really knew the material.

Here is a comment from a student who did not find the in class WOD helpful:

- I personally don’t think having the in-class graded WOD was helpful for learning since learning new material takes time, practice, and continued usage until that new material becomes natural.

Did WODs help you become more confident in your software development capabilities?

80% of the students surveyed responded that WODs increased their confidence. Comments include:

- Yes. Working under pressure is something that I have not experienced much of. In the real world, there are deadlines, some of which are unfair (My brother works as an architect, and he has told me this numerous times). Thus, its imperative that one learns how to perform efficiently under pressure, when stakes are high (100 points is a lot!)

- I do. It’s allowed me to think on my feet faster and approach problems in a calm and level manner.

- Not so much at first since I didn’t do too great at first, but the more WODs I did, the more confident I did and my performance improved too.

- Before taking this class, I definitely lacked in my software development skills. I still have lots of room for improvement, but the WODs and the athletic software engineering learning style definitely forced me to put more effort into practicing, learning, and ultimately improving such skills.

- Yes, each time I have successfully completed a WOD, whether easy or difficult, I felt accomplished and more confident in my software development capabilities.

- Doing WODs has definitely made me more confident about my software development capabilities and my understanding of JavaScript. When I got to the JavaScript section of my company interview, I was praying to God that it was similar to ICS 314– which it sorta was (minus the functional programming and Meteor part).

Those who did not find it helpful noted:

- Eh, didn’t really change. Always feels good when you can solve a software related problem, always feels terrible when you can’t.

- Not really. It just forced me to actually understand the material before the WOD.

Did WOD-based homework help you to be more focused?

79% of the students surveyed responded that WOD-based homework helped them to be more focused. Comments include:

- Yes, I found that I was consistently focused throughout all of my practice WODs because I had a sense of duty to finish it all in one go. Seems like some sort of mental conditioning.

- One of the biggest problems for me is finding the motivation to actually start on my homework. Because the WODs were so frequent, I was compelled to just finish all my homework after I had started my WOD. I really love the WODs!

- The WOD-based homework assignments definitely helped me to be more focused while doing homework. Doing homework seemed like less of a chore and more of a competitive challenge. It was easier to gain motivation for the homework because I could know that I would be finished with my homework within a rough time period. I could set aside double the DNF time for homework and know that I will take no more than that amount of time to complete the assignment.

- I feel like I had a decent work ethic before this class and this class helped reinforce that. The length of the assignments were doable in one sitting and usually required your undivided attention. I feel like if the assignments were any shorter, then enough content could not be covered, if they were any longer, then not as much focus and concentration to get it done in one sitting would be used.

- Yes, the practice WODs allowed me to hone my focus on what to study for rather than reading a book that shows theory. The constant coding was an excellent way to actually learn how to code.

On the other hand:

- Not really because there is still potential to have distractions since the practice WODs are on the computer.

- No, I was extremely distracted the entire time, and I simply moved through the video while multitasking.

6. Student evaluation of ICS 314, AY 2016-2017

As noted above, the “athletic” portion of the class covered approximately the first 10 out of the 16 weeks of the semester. The final six weeks focused on applying these skills to the development of a real world application, and (hopefully) wrestling with the resulting design and process problems. So, some additional insight into ASE might be gained by reviewing the end-of-semester course evaluation data. Since 2007, I have been publishing all my course evaluations without any editing, and they are available for review here. The following presents a subset of AY 2016-2017 course evaluation data that seems most relevant to this essay.

119 students completed ICS 314 across four sections during AY 2016-2017. 115 of them completed the end-of-semester course evaluation, for a response rate of 97%.

There are three Likert Scale questions that seem particularly relevant to this essay:

| Statement | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The instructor fulfilled the goals of the course | 1 | 1 | 1 | 30 | 81 |

| I gained a good understanding of concepts/principles in this field. | 1 | 1 | 9 | 29 | 75 |

| The instructional materials (e.g., texts, handouts, etc.) were relevant to course objectives. | 1 | 0 | 3 | 32 | 77 |

These responses indicate that at least 90% of the students surveyed agreed or strongly agreed with each of these statements.

The free response data is harder to summarize in a useful manner. Here are two comments that I find particularly revealing:

-

A very rewarding course if one has the motivation to put time into it. Focuses on web application development through JavaScript/HTML/CSS. Great class to hone your skills if you are somewhat knowledgeable in these areas. If not, you WILL learn it. Depends on one’s individual coding skills which will dictate how much work needs to be put in. It is totally brutal if one is a total beginner since you are only given a week to learn new concepts on your own from scratch and use your skills the following week to implement what you “learned.” Making friends with others so you have someone to reach out to would help tremendously so you don’t end up getting swamped by stuff. Professor seems very open to providing help though, but asking peers is probably more within many student’s comfort zones. If you really don’t know it, you MUST ask for help. There is no time to spend hours figuring out a basic concept on your own, especially since you have other classes and you will be ‘expected’ to know it later on. I am a strong coder myself though, and kept up just fine, without watching all of the video tutorials. It leans more towards an independent study online class with actual class time just being dedicated to WODS/questions/project work/get to know your peers. No paper exams or textbook to study. TLDR: Not for the weak. Best class for aspiring web developers. Help is always available. (Fall 2016, Section 002)

-

…for the first half of the semester I questioned whether this was a software engineering course at all. I learned how to code in Javascript, make basic web pages, and faff about with a web framework. It was only when we got to the final project that it felt like we were learning anything about software engineering (and actually learned said web framework for real). Here the first half of the course came to make sense as buildup towards actual software engineering in the form of the final project. I think the final project was the best part of the course. I strongly believe that the best way to learn something is by actually doing it. (Spring 2017, Section 002)

7. Conclusions

After four years of using Athletic Software Engineering in the classroom, I find it to be the most effective method I have discovered so far for teaching students the basic skills necessary to experience real world software engineering design and process problems. Perhaps counter-intuitively, student feedback is very positive, despite the pressure and intensity of the pedagogy. This, ultimately, does not surprise me: as long as the rewards appear commensurate with the struggle, most students are willing to work hard.

That said, I see many, many opportunities for improvement to the course. I want to develop technology to simplify the development of professional portfolios, which should resolve some of the problems encountered by some students. I want to provide more practice WODs, and improve the pedagogical quality of the current WODs. There are some additional software engineering concepts (including continuous integration, performance evaluation, and design patterns) that I would like to introduce if time permits. Just keeping the materials current with the fast moving world of software engineering and application development requires constant investment of time and energy.