Athletic Software Engineering

12 Jul 2013How startup weekend, outrigger canoe racing, and Crossfit inspires a new approach to software engineering education

I have a confession to make. For over 20 years, I’ve been teaching “cubicle” software engineering. This does not mean that I teach students to use punch cards, COBOL, and the waterfall lifecycle model. To the contrary, my curriculum appears quite modern: agile development processes, a “flipped” classroom, and modern tools and technologies including GitHub, CloudBees, Bootstrap, and the like.

When I refer to cubicle software engineering, I refer to two pedagogical decisions I have not changed in 20 years:

- A software development timeframe measured in days, weeks, and months.

- No explicit focus on the actual speed of coding.

Cubicle software engineering reflects current industry practice. Consider a popular modern methodology, such as Scrum. Each day begins with a standup meeting, where developers report on the development tasks that they have, and haven’t, accomplished. Based on this information, the team reassesses their priorities, and over time derives an estimate of their development “velocity”. Developers are free to work as fast or slow as they want; management is prohibited from complaining about their “speed”.

In the past few years, a different style of development has emerged within the context of hackathons and startup weekends. The relevant characteristic of these events is that they take place over 24 to 48 hours, and thus a “slow” developer is a significant liability to the team. In industry, where the development timeframe is measured in weeks or months, a “slow” developer could potentially compensate by working a few extra hours on nights or weekends to increase their “effective” speed. During a startup weekend, on the other hand, there are no “extra” hours, and slow developers are just plain slow.

I recently looked at the projects created during a Honolulu Startup Weekend, and realized that the tools and technologies I teach my students provide an excellent basis for success. But what I don’t teach my students is how to use these tools to code fast: how to start with nothing and create a functional and interesting web application in a matter of hours. In fact, I teach the opposite: I give my students significantly more time than required in order to remove time as a factor. I give my students a week for a programming assignment that might take me an afternoon to finish. As a result, I believe my students are intimidated by a startup weekend, as the very idea of coding at a breakneck speed falls completely outside their software development experience and training.

I now believe that in order for my students to feel comfortable participating in a startup weekend or hackathon environment, they need to train for it. And this means not just learning useful languages, technologies, and design patterns, it also means learning to code fast. It means instead of thinking of development in terms of days and weeks, they think in terms of hours and minutes. Instead of giving them multiples of the time required, I should regularly put them into situations where they must code as fast as they possibly can. In other words, students need to engage in software development as an athletic activity, not a (sedentary) cubicle activity.

Wait a minute. Is athletic software engineering the right educational goal?

It is not unreasonable to question whether or not athletic software engineering is an appropriate pedagogical goal. As noted above, it is not part of mainstream software development culture, and the most obvious measure of coding speed, LOC/hour, is a canonical example of measurement dysfunction in the field of software metrics. Before explaining how I plan to implement athletic software engineering, here are the educational benefits I anticipate from the approach:

(a) Athletic software engineering education avoids the verisimilitude problem. Software engineering is far too vast to cover in a single semester, and so all teachers pick and choose what to cover based upon some sort of organizing principle. In my current approach, I find myself saying the following all too often: “For this particular assignment, you might think doing [X] is not that important, but when you’re out in the real world you’ll be glad you learned about it”, where [X] could be anything from a user guide to the JavaDocs to issue management.

Athletic software engineering, in contrast, results in a different organizing principle: developing the skills to succeed in a startup weekend environment. My hope is that this organizing principle hits a sweet spot: complex enough to fill a semester with interesting software engineering principles, simple enough that most students can accomplish the goal in a single semester.

(b) Speed does not mean sloppy, it means fluency. There is a perception in software development that people who code fast are cutting corners and creating low quality work. Athletic endeavors are the opposite: the best athletes are fast precisely because they have the best technique and greatest efficiency of movement; in short, fast means quality.

I believe that teaching students to code at high speed is also teaching them to be fluent with their tools and technologies, and to make less errors rather than more.

(c) The flow state as normal state. The programming culture reveres the “flow state” as a semi-mystical occurrence where deep, uninterrupted concentration makes time pass quickly, banishes all distractive thinking, and allows bursts of creativity. It is viewed as an elusive and transitory phenomena.

In my experience as a competitive paddler, the “flow state” is absolutely mundane and predictable. When the starting gun goes off, you and all the other paddlers around you enter a state that is pretty much indistinguishable from the programming flow state, and it lasts until you cross the finish line. This is just as true for quarter mile sprints that take four minutes as it is for distance races that take four hours.

I believe “flow state as normal state” will also be true for athletic software engineering education: give students a programming problem and very little time to solve it, and they will enter the flow state and stay there until they either finish the problem or run out of time.

(d) Solving the multi-tasking problem. A modern educational problem is multi-tasking: there is mounting research evidence that multi-tasking impairs learning.

Athletic software engineering education solves the multi-tasking problem by (a) creating a sense of urgency which (b) creates the “flow state” (see above) which (c) removes the desire to multi-task.

(e) Group training for competition spurs excellence. Spectators watching athletic competitions see only a sliver of the total picture. For each hour that an athlete participates in a competition, there are tens or hundreds of hours of training where the competition is not to win, but to get better. Training in a team has significant psychological and motivational benefits: the presence of others working hard motivates you to work hard, and the performance of others provides benchmarks.

The athletic software engineering classroom will strive to create that same esprit de corps through shared exertion, commitment, success, and failure.

Implementation

Implementing an effective approach to athletic software engineering education in the classroom will be difficult. Here are the key implementation concepts I will be assessing during Fall, 2013 in my software engineering course.

(1) Workouts, not classes. First, I will refer to my face-to-face interactions with students as “workouts”, not “classes”, as a way of reframing expectations for classroom hours. Students will not come to class to passively listen to me impart information. Instead, they will come to class in order to engage in structured activities intended to assess and improve their ability to develop software quickly. This leverages my development of flipped classroom techniques for software engineering over the past five years, where my “lectures” were designed to be seen (via YouTube) prior to class, not during it.

(2) Code Racing: the new normal. A standard component of a workout session is a code race: a timed programming task performed by all members of the class with a simultaneous start time and a recorded finish time. Regular code racing is extremely important to developing speed, as the presence of others simultaneously attempting to complete the same task in as short a time as possible creates motivation.

I will not grade students on their code race results. Instead, I plan to give tests approximately once a month which are time-delimited, requiring students to have developed a threshold level code speed. This makes racing indirectly relevant to their course grade. I want to make racing interesting, fun, and motivating for students, and as a result, make the startup weekend attractive to them as a place where they can show off their newfound skills.

(3) All races have an Rx time. In CrossFit, the workouts have an “Rx” (or “as prescribed”) specification, which is generally very difficult to achieve, along with various “scaled” versions which are easier to achieve. Software engineering workouts also have an “Rx” specification, which is expressed as “time to completion”. The Rx specification will be determined by having the instructor complete the task prior to assignment to students.

Having a specified Rx provides two benefits. First, it gives students a concrete, achievable goal to work toward with respect to their code speed. Second, it provides a way to normalize workout results over time. Given that the tasks will vary in complexity from day to day, an “average” workout time (or trend in workout time) over the course of the semester is clearly meaningless. On the other hand, trends in the ability of students to achieve Rx over the course of the semester are more likely to be meaningful.

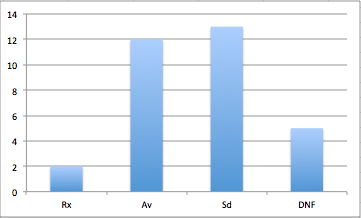

(4) Leveling up. CrossFit Kailua expands upon the Rx specification with two additional, easier specifications: Av (Advanced) and Sd (Standard). This provides new (and/or less athletic) CrossFit members with more obtainable specifications. In addition to the Rx time, I will provide an Av time (150% of the Rx time) and an Sd (175% of the Rx) time. This is particularly useful in the case of undergraduate students, who might never achieve an Rx during the course of the semester, but who might take pride in consistently achieving Sd or Av specifications.

(5) Scoreboards for motivation, not humiliation. Even though races are not used for grading, publicizing a standard scoreboard, with names (or even pseudonyms) along with race performance creates a significant risk of humiliation for the slow students, who will be obvious from the public nature of the races themselves. On the other hand, providing feedback on how you are doing relative to others provides motivation to improve.

To minimize humiliation while providing motivation, the scoreboard will not list individual performances, but rather the aggregate number of students who achieved each of the three levels (along with those who “DNF’d”, or did not finish because time ran out). For example:

With this type of scoreboard, students will know which level of performance they achieved for any given race, and thus how they relate to others in the class, without being singled out as best or worst.

(6) Warmups. CrossFit workouts begin with a warmup session in which coaches lead the class through the fundamentals of each movement using a very light PVC pipe instead of a barbell. No matter how experienced the students, the fundamentals are always reviewed every time. Similarly, each athletic software engineering workout will begin with the instructor leading the class through a simplified version of the workout to stress the fundamental tasks to be completed.

(7) Individual and group-based races. Races will not only involve individuals, but also pairs of students in order for them to experience group work at speed. The pairs will be randomly assigned by the instructor; students cannot “cherry pick” partners in order to improve their performance. In outrigger canoe paddling, there is the concept of “blend”, where paddlers collectively reach peak efficiency working together. A challenge is to teach, assess, and recognize “blend” in the context of group athletic software engineering tasks.

(8) Learning the skill is separate from performing the skill. It is not useful to give students a task for which they lack the required skill set and then time their completion of the task. For example, assume the task is to create a github repository, push a webapp’s code into the repository, then set up continuous integration and deployment of that system using a cloud-based service. If the student has never done that task before, it could take many hours of research to figure out all of the steps and perform them successfully for the first time. On the other hand, this same sequence of steps is a canonical pattern that an experienced developer could accomplish in minutes given fluency with all of the associated technologies (i.e. in the case of this class, the technologies include Java, Git, GitHub, Play Framework, JUnit, Eclipse, Jenkins, MySQL, and CloudBees). There is easily a 100x difference in speed between novice and expert on this task.

To separate “learning” from “performing”, the class separates “homework” from “workouts”. Each workout is prefaced by assigned homework, in which the students are provided reference material and sample tasks they can use to learn how to perform the task. Then, in class, the “workout” assesses their ability to complete the task in an efficient, rapid, and correct fashion.

(9) Importance of skilled coaching and individualized feedback. Athletic software engineering education demands significant skill and expertise on the part of the instructor. First, the instructor must be able to develop an appropriate sequence of homework assignments and in-class workouts. Second, the instructor must determine the Rx times. Third, the instructor should be able to monitor students and provide feedback on how they can improve their performance on the task over time.

(10) Motion capture. In athletic endeavors, a common training tool is to take video of the athlete performing a task, then analyze the movements to see how they could be improved. This approach appears promising for athletic software engineering. I am currently experimenting with the free version of Rescue Time to see if the data it produces can support useful “time and motion” studies of software development.

For example, if a student is spending a high proportion of their time doing google searches during the completion of a task, then they are probably in the “learning” phase and have not achieved mastery.

(11) Startup weekend (or hackathon) as final exam. It would be ridiculous to give students a written final exam; that’s not what they’ve been spending the semester training to accomplish. Instead, the course will include a startup weekend or hackathon as the culminating experience so that students can apply their training to a real-world event.

(12) Athletic software engineering education cannot be MOOCed. Massively open online courses are an important breakthrough in education, which can make certain types of learning available at scales previously unattainable. My hypothesis is that athletic software engineering is not amenable to a MOOC environment. Similar to athletic training, very few people have the internal motivation to “train” alone and in physical isolation from others. My personal experiences with CrossFit and outrigger paddling indicate that, for me at least, my development of those two skill sets would not have happened without a group setting, excellent coaching, and face-to-face interaction with coaches and other “students”.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to my coaches at Kailua Canoe Club (Kamoa Kalama, Hank Leandro, Kawai Mahoe, and Doug Borton) and at CrossFit Kailua (Erik Alvarez, Matt Kubick, and Levi Daniels). Who knew you were also teaching me about software engineering education?